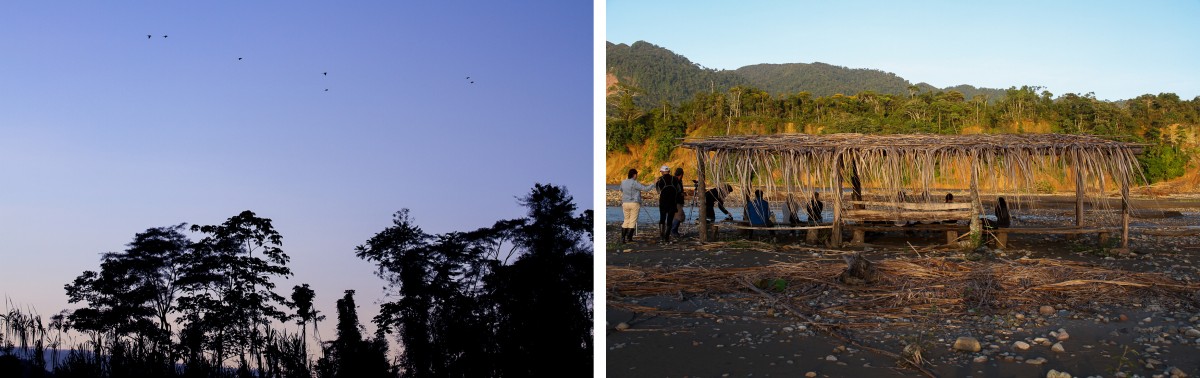

It’s five fifteen in the morning and a thin mist hovers over the Alto Madre de Dios River. The Amazon has been awake all night but this group of bleary-eyed volunteers is still rubbing sleep out of their eyes as they board a crees boat to cross the river.

They arrive at the beach hide in front of the Manu Learning Centre (MLC) Reserve just as the sun begins to peek up from the lowlands to the east, it’s warmth dispelling the mist they had travelled through. Before long, the entire length of the river’s edge opposite the hide has been painted a golden yellow and the colpa – or clay lick – is in full view. A single pair of chestnut-fronted macaws calls out from above as it soars towards the colpa, and within minutes, those calls multiply as tens of macaws flock to it for their morning feed.

Leaning over a clipboard of data sheets, Conservation Intern, Maria Chávez, puts her pencil down and lifts a pair of binoculars to her eyes. As part of the Blue-headed Macaw Project, a long-term study that has been running out of the MLC for nearly ten years, Maria and her colleagues regularly visit the colpa in order to monitor the abundance, diversity, and numbers of both blue-headed macaws – listed as a vulnerable species on the IUCN’s [International Union for the Conservation of Nature] red list – and other bird species.

“If we can get the word out there that the Blue-headed Macaw is suffering from human disturbance or whatever other reason, we can use it as an umbrella species to also help conserve the area for both the blue-headed macaw and other species of bird,” Maria explains.

Among the main threats to the general macaw population in the Manu Biosphere are habitat loss due to deforestation, exploitation in the pet trade, and human disturbance – which is why the project also monitors tourist activity in the area.

Ecotourism is a growing industry in Peru and is one that has had a positive impact on both the country’s national economy and its environment. But this increase in activity has given rise to more noise pollution due to tourist boats and there is now a greater possibility that visitors may unknowingly disturb the macaws’ habits by, for instance, wearing bright colors or taking flash photography.

“Whenever tourists come to the beach hide, we always try to talk to them after they’re done observing the birds to tell them about our study,” Maria explains. “We try to get them interested and raise awareness because ecologically, macaws are part of a really delicate system and anytime that we disturb it, we’re making a much larger impact than we initially believe.”

“At the same time, even if we see a correlation between the decline in birds and the rise in numbers of tourists, we don’t want to tell people that tourism is bad because it would really damage some peoples’ lives – many Peruvians depend on these jobs,” she continues.

Using the data collected, one of the long-term goals of the Blue-headed Macaw Project is to be able to develop a plan together with the tourist companies that frequent the Manu Biosphere. This plan would seek to both educate visitors about the potential impact of tourism on the macaw population in the region and, consequently, encourage conscientious behavior while bird watching.

But before any of this can happen, the MLC first needs evidence of the correlation between the declining number of macaws and the rising number of tourists.

“We are sorting and organizing through years of data to be able to compile it into one file that’ll give us an idea of the trends so that we can reflect the results to the public,” Maria explains.

In the meantime – and with the outcome of this study possibly years away from being realized – Maria makes sure to enjoy every opportunity that she has to observe Manu’s unique bird population when she’s out at the colpa.

“Macaws are really charismatic birds that help preserve that image of diversity and beauty that we have here,” she reflects.

“It’s especially exciting to see Blue-headed Macaws because they are becoming more rare. Seeing them flying about in the morning is uplifting to see, to know that they are still present.”

Text & photos by Katie Lin