Two years ago, Lawrence Whittaker left his home in Hampshire (UK) to pursue a research internship with the Crees Foundation, here in the Peruvian Amazon. Then, a recent graduate from The Open University, Lawrence is now a senior field staff member at the Manu Learning Centre.

When he’s not leading surveys or getting caught up on data entry, Lawrence has been working hard to establish himself as a biodiversity researcher, most recently becoming a first time, peer-reviewed published author.

The Crees Foundation’s journalist, Katie Lin (KL), sat down with Lawrence (LW) to discuss the topic of his and his colleagues’ paper in more detail.

KL: You’re a staple presence here at the Manu Learning Centre, Lawrence! But let’s go back to the beginning of your relationship with the Crees Foundation. How did you first find your way out here? And what was it about the jungle that has kept you here?

LW: I was looking to do a bit of travelling after finishing my degree. So, I looked at conservation-related and biology-related internships and I found Crees. The Amazon sounded like an amazing place to go to.

And what’s kept me here is the sense of being part of something that has a moral principle. You get a big sense of achievement out of the work that you do here – it’s very tangible.

KL: When most people think of the Amazon jungle, they’re probably not picturing hectares of dense bamboo! And yet, your research for this paper entailed the use of bamboo traps and took place entirely in the bamboo forest of the Manu Learning Centre Reserve. Tell me more about the topic of your paper and what ecological information your research has revealed.

LW: The topic of the paper is about two neotropical frog species that are fairly understudied: the Osteocephalus castaneicola and the Pristimantis olivaceus.

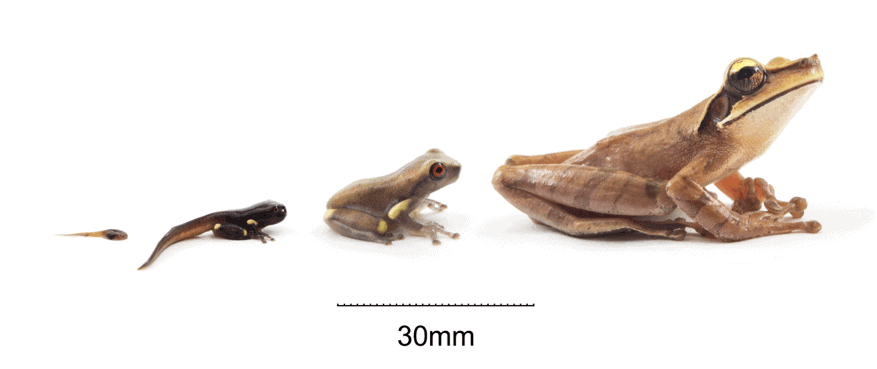

For the Osteocephalus, we found out information about its breeding season, so the time of year that it is going to lay its eggs and then roughly how long it takes for them to develop into frogs. Breeding peaked around October then dropped off after that.

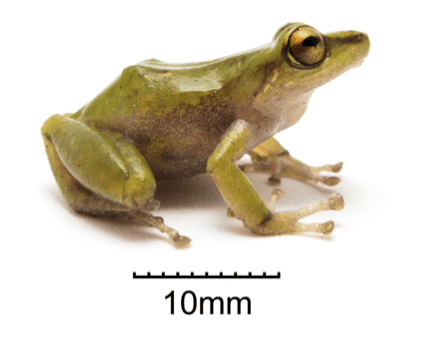

As for the Pristimantis, this was a species of frog that we found specifically hiding in bamboo during the dry season as refuge. During the wet season, there are small streams that appear and in the dry season, they will completely disappear so the forest dries out quite a bit. Also, other insects will use the water [that] the bamboo holds to breed in and belay their larvae there, providing a source of food for the frogs and tadpoles. So, there’s a concentration of food in one place.

KL: What motivated you to use bamboo traps in this unique pilot study?

LW: Bamboo is easy to manipulate and easy to source, so you can go into the jungle, cut it down, and craft a cup shape out of it. So, you can set up a study quite quickly and easily [using bamboo traps] and you can still get reliable data.

KL: From the field research stage to writing up final drafts, what did each stage of this project look like?

LW: The research was simple. We set up 14 traps and we’d go around and check them. If they had eggs or tadpoles, we’d write “Yes”. There was one occasion where we brought tadpoles back and reared them to find out what frog [species] they were, but we were mostly looking at where we caught them, whether or not eggs or tadpoles were present, and if frogs were present.

We kept a record of this data and looked for patterns, such as that of the breeding season. From there, we wrote up our method, our findings, and a brief history of the frog species.

Originally, the intention was to find a couple of species of frog that we know should exist here but the traps didn’t catch these frogs. However, they did show us other information.

KL: Field research can be a very exhausting process – and yet, here you are, two years later continuing to conduct surveys in the forest. What motivates you as a researcher?

LW: Knowing that I’m contributing to a body of knowledge that’s fairly under-researched. It’s very motivating.

It feels like we’re inching towards helping to save this place, Manu, the Amazon – but it could be any other tropical forest around the world – and getting more people engaged.

KL: It’s clearly an enormous accomplishment to become a peer-reviewed published author at this stage in your career. So, if you’ve given it any thought at all, what are the next steps for you?

LW: It’s difficult to put a solid plan in place, but I’d like to do a masters in sustainable management and conservation and just carry on learning.