When Alice Brown arrived at the Manu Learning Centre as an intern in 2012, she hoped for an educational experience that would allow her to both apply her undergraduate degree in Environmental Sciences in situ and give her a taste of fieldwork.

Nearly three years later, in September of this year, Alice left her position as the Crees Foundation Education Field Coordinator in order to pursue a master’s in Conservation and Biodiversity at the University of Exeter – and in the same month, she became a peer-reviewed published author for the first time. The Crees Foundation’s journalist, Katie Lin (KL) caught up with Alice (AB) about this amazing accomplishment and the exciting find that is the subject of her and her colleagues’ paper.

KL: Let’s go back a bit. You have quite a strong tie to the Crees Foundation – and how could you not after spending more than three years at the Manu Learning Centre! What was your first experience with Crees like? And what was it about the jungle that kept you out there?

AB: My first experience was a genuinely life-changing one. I had wanted to work to protect the rainforest since seeing a video about deforestation in geography class at school, so I always knew it was what I wanted to do. I did A LOT of research to find an organisation I really believed in and that I would be proud to work for.

My time as an intern with Crees was fantastic! I learnt so much, and it was incredible to work with the whole team everyday out in the forest on all of the projects that Crees was involved in at the time: the long term biodiversity monitoring, as well as stage one of the GROW [community] programme. Every single person that works for and with Crees is incredibly passionate and hardworking, and it’s great to work with such a great group of people. I felt really involved with the work, as I was out there doing it everyday and seeing the results.

I loved everything about the jungle – even the swarms of insects, constant sweatiness and lack of contact with the outside world. There is no way to put in to words how overwhelmingly impressive the jungle is to someone [who] hasn’t been there. It is the most complex and diverse environment on the planet. Everything has its own unique role to play, even us humans. I think just my love for working and just being in the forest, coupled with knowing that there is always so much more to do to help conserve it, are what kept me out there.

KL: During your time at the MLC, I’m sure you’ve seen an incredible variety of animals – and just when you think you’ve seen it all, you capture a Blue-fronted Lancebill! Tell me more about this bird and why its capture was so exciting.

AB: Well that’s the interesting thing – there really isn’t much information about the Blue-fronted Lancebill, or neo-tropical hummingbirds in general. Because they are such a diverse group, hummingbirds are often understudied, even though they are incredibly important for ecosystem function in tropical forest.

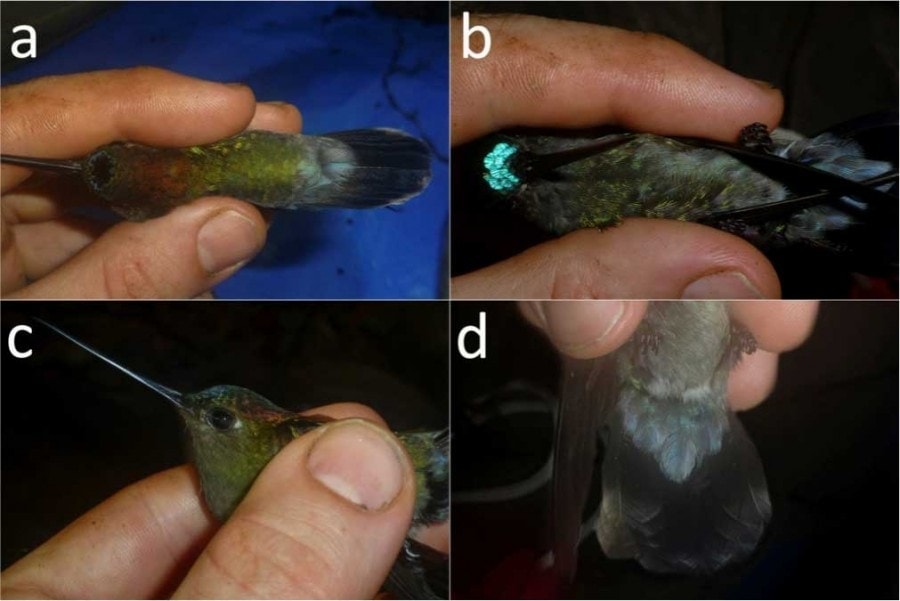

That’s why using mist-netting, the method we used to capture our individual, is so good. It basically allows us to capture smaller, often secretive understory birds that can be incredibly difficult to identify by their call. Mist nets are very thin nylon nets that are suspended between two poles. They are almost invisible to many birds, and when a bird flies into the net a trained mist-netter can extract the bird and identify it ‘in-the-hand’. This method can also tell us a lot of other things about the bird, including its age, sex, and whether it is breeding or not.

So this can be a really good way to assess species diversity and abundance, as well as demography in a particular area. It can be especially useful in a tropical forest environment, where the dense foliage makes spotting and identifying birds that much more difficult. The Blue-fronted Lancebill is one of only two species in the genus Doryfera, and it is has been recorded in Brazil, Colombia, Guyana, Ecuador, Venezuela and Peru. Until we captured the female Blue-fronted Lancebill, it had only been recorded in northern and central Peru, so it was incredible to find it 470km southeast of where it had [only] ever been seen before!

KL: It must be so gratifying to see all of your hard work wrapped up in a single, published article! From the field research stage to writing up final drafts, what did each stage of this project look like? And how long did it take to complete this paper, start to finish?

AB: Yes, it most definitely is. There is a huge amount of preparation, writing and editing that goes into a publication, even a small note such as the Blue-fronted Lancebill paper. I was asked to work on the note when I became a member of the field staff team, so that was really exciting.

Anyway, in terms of the fieldwork, that’s the easy and fun bit. Once the field team captured and identified the female Blue-fronted Lancebill during a mist-netting session, we needed to verify how much of a range extension our record was. This meant searching for every record of the bird in the world – ever. That took some time and very thorough searching, but in the end I found 196 records, then used Google Earth to locate the grid reference for each one. We already had a basis for the text by this point, so then it was a case of sending the records with their grid references off to Oliver Burdekin, one of the co-authors, who is quite the whiz at GIS [geographic information system]. He produced the map of the current distribution of the bird, and then, using habitat, climate and other variables from its known distribution, used a modelling programme [to] predict and map its potential distribution.

The thing with tropical rainforests is that there are such a huge number of species, that not many people study one species specifically, especially in a place like Manu, which has such a huge diversity of birds. This means, often we don’t know what a species’ full range is because nobody has been specifically looking for that species. That’s where models (as well as more research!) come in handy. In total, it took us about 15 months to write and have the paper published – a lot of that time was because I was in the field!

KL: There’s a lot more work that goes into scientific research than most people would realize…but as you and I both know, there are also always a lot of passionate researchers out there willing to go the distance and get sweaty! What motivates you as a researcher?

AB: Knowing that the data I am collecting is ultimately valuable for everyone, everywhere; the results of the work we do help to add to the knowledge base about tropical forests and their conservation, which matters to everyone because we rely on them for our existence.

It also motivates me to know that every time I go into the forest I will see something new. No two days are ever the same and there is ALWAYS something to learn.

KL: Well, you may have left the tropics for the time being, but hopefully this won’t be the last publication we see from you! What is your plan now?

AB: Absolutely not. There is currently a paper under review [on] historical human disturbance effects upon biodiversity in the canopy using rainforest butterflies. I am one of the co-authors on the paper, which forms a chapter of Andy’s [Andrew Whitworth, Crees Foundation Research Manager] PhD. I am also co-authoring a paper on a comparison of butterfly surveying methods, alongside other members of the Crees team.

I will be doing my masters until next September, during which time I will be conducting and writing up my research project and getting plenty more experience working with British wildlife, both on land and in the sea. Then…who knows, there are plenty of options out there, and I will be looking into them over the coming year. Rest assured though, I will most definitely be returning to the rainforest someday soon!