Last weekend, a team of us camped out on the Piñi Piñi mountain to explore the wilderness and wildlife on our doorstep.

Our nature reserve in Peru’s jungle sits at the foot of the Andes mountains and as these ecosystems collide they create a thriving melting pot for a diversity of wildlife.

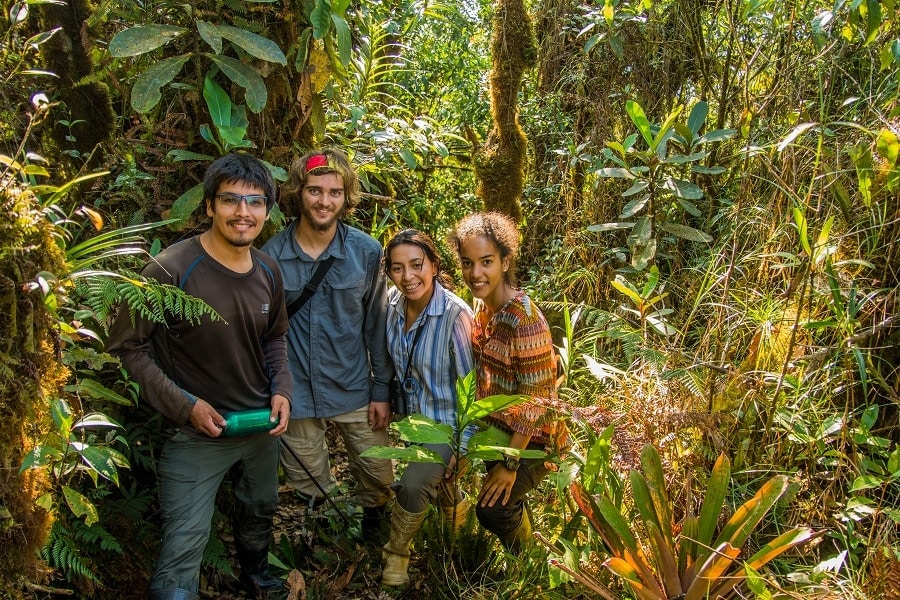

Despite spending six days a week trekking through the jungle to monitor, survey and collect data in the heat and humidity of the tropics, our team of researchers and volunteers here at the Manu Learning Centre (MLC) rarely get tired of exploring.

Late last Saturday afternoon we rushed to finish off the week’s work so that we could head out into the jungle again and spend our day off discovering lesser known spots.

Night fell as we reached the back of the MLC reserve, where the forest opens up and the trees loom larger. Here we began the steep two hour scramble over the rocks and roots of the Piñi Piñi.

With machete in hand, Jackie leads the way while hacking at the vines that twist across the trail. Small and slight, Jackie is one of the Peruvian field staff here at the MLC and is carrying out research into the wonderful world of fungi.

Suddenly she stops, dead. She’s staring at a patch of leaf litter on the trail just in front of her and with a cautious hand movement beckons us forwards. “Keep two meters distance,” she warns us. This is the protocol for when we come across a snake in the field and sure enough as we creep to Jackie’s side we see the vibrant red, yellow and black scales of the serpent.

Although docile and secretive, this coral snake is highly and deadly venomous. Predominantly coral snakes have a neurotoxic venom that acts on the nervous system and finally paralyses the repository system of the victim. But by keeping a safe distance we happily snap photos as this unaggressive and strikingly beautiful serpent slithered away.

At 7pm we reach our camp, half way up the Piñi, and our group splits in two as some start collecting wood for a camp fire while others string up the hammocks. Soon we’re wolfing down our box dinners around the golden glow while listening to the rustles and crashes coming from the darkness.

After food, we head out on a night walk in search of frogs and snakes. Jackie tells us about some of the medicinal properties of plants we come across and collects samples of weird looking fungi.

The moon is bright and the forest is unusually quiet. After a couple of hours searching, we’ve found nothing and give up. Wildlife hunting is unpredictable.

The next morning, our tired legs are stumbling up the steep slope by 4.30am. Sweating in the darkness we push on, eager to get to the look out point before sunrise.

As we reach the plateau and the jungle sweeps down below us, a reddish glow stretches across the horizon. We sit hungrily tearing off chunks of bread while watching the flaming ball of morning sun creep higher.

With the whole day ahead of us, we’re in no rush to head down and decide to climb a little higher. It’s not long before we’re hacking our way through cloud forest draped in mosses and lichen. We reach another look out point that reveals the silvery snaking ribbon of the Piñi river below.

There are groups of Machiguenga native people living alongside the river who are only in the first phases of contact with the outside world; they keep their traditional lifestyle but make contact for medical care and commodities, such as metal tools.

The Machiguenga are the largest group of native people in the Manu region, numbering about 1,400 people, and they have extensive family networks that allow the uncontacted groups – namely the Kugapakori and Kirineri – to communicate with other contacted groups.

Looking out over the Amazon, it’s heartening to know that there are still wildlands where people and nature are relatively untouched by the outside world.

With the sun now high in the sky, we decide it’s time to head back to camp for lunch but the forest has one last treat for us. As we clamber down from the mountain, a troop of Peruvian woolly monkeys swing through the forest just above our heads, with the alpha male keeping the youngsters in check.

These woolly monkeys are an Endangered species that are severely understudied. The Crees Foundation have been funding research into them here at the reserve so that we can better understand the threats they face and plan conservation strategies for their future survival.

The MLC reserve is one of the few easily accessible areas where you can monitor Peruvian woolly monkeys, as there has been no hunting here for decades so the monkeys are less timid of people and accept them much more readily. We’re privileged to get regular up-close sightings of these beautiful beasts.

Although it was just one night, the Piñi Piñi microadventure reminds us of the rich diversity of nature and culture on our doorstep.